Fr. William Cunningham leads an annual Walk for Focus: HOPE in Detroit in the early 1970s. Sacred Heart Seminary's activism intensified in 1965 after the police attack on civil rights marchers in Selma, Alabama. Several Sacred Heart faculty members, including Cunningham, flew to Selma to join the second march with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (Courtesy of Focus: HOPE)

When Detroit Archbishop Edward Weisenburger in July fired three Sacred Heart Major Seminary professors known for their past criticisms of Pope Francis, it marked another turning point for the 106-year-old institution.

Over four decades, Sacred Heart evolved into a conservative, right-wing Catholic seminary, much of the time under the influence of recently retired Archbishop Allen Vigneron.

Vigneron has deep ties to the seminary as an alumnus, former professor, dean, rector, and eventually the archdiocese's leader.

Weisenburger's removal of the professors — Ralph Martin, Edward Peters and Eduardo Echeverria — signals a sea change in the diocese, suggesting a more progressive tone for both the seminary and the archdiocese. Since becoming archbishop in March, Weisenburger has restricted the use of the Latin Mass and emphasized social justice for migrants, notably marching to protest aggressive ICE raids and policies.

Detroit Archbishop Edward Weisenburger joins other clergy during a procession from Most Holy Trinity Church in Detroit's Corktown neighborhood to the ICE Regional Field Office on Michigan Avenue in downtown Detroit July 14, 2025. The procession was organized by Strangers No Longer, a Catholic grassroots immigrant rights advocacy group. (OSV News/Detroit Catholic/Valaurian Waller)

Weisenburger's recent actions echo an earlier chapter in Sacred Heart's history, when the seminary was a hub of unprecedented progressive activism in the 1960s, when Vigneron himself was a seminarian.

"The seminary was opening its doors and windows to the world," said Harry Carson, a philosophy professor at Sacred Heart from 1965 to 1990. Carson taught contemporary philosophy and explored the intersection of faith with topics like racism, war, technology, and environmental crises.

"The world was turning upside down in this country," Carson said in an interview.

A circa 1970s black and white photographic print depicts Sacred Heart Seminary from the corner of West Chicago Boulevard and Linwood Street in Detroit. A statue of Mary sits in the corner of the lawn. (Courtesy of Detroit Historical Society)

During the '60s as the Vietnam War escalated and racial unrest shook the country, the formerly insular seminary was awakening to the social problems outside its Gothic, fortress-like building in the heart of a neighborhood rapidly changing to majority Black residents.

In 1962, Pope John XXIII convened the Second Vatican Council, calling for aggiornamento — an updating of the church and its engagement with the world. John XXIII called for the church's social doctrine to "be known, assimilated, and put into effect in the form and manner that the different situations allow and demand." He called for the doctrine to "be studied more and more," and specified that "it should be taught as part of the daily curriculum in Catholic schools of every kind, particularly seminaries."

Archbishop John Dearden of Detroit responded to that call from John XXIII by inviting seminary rectors from across the U.S. to Sacred Heart for a conference on implementing liturgical reforms, including the shift to English-language Masses.

Advertisement

Progressive activism in 1960s

The seminary's activism intensified in March 1965 after the violent police attack on peaceful civil rights marchers in Selma, Alabama. Several Sacred Heart faculty members — including Fr. William Cunningham and Fr. Jerry Fraser — flew to Selma to join the second march with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Meanwhile on that same day in Detroit, Msgr. Francis X. Canfield, Sacred Heart's rector, led some 400 seminarians and faculty in a 6-mile march downtown to join thousands of other protesters. They carried banners adorned with the seminary's "Rampant Lion" emblem and the call for "Christian Justice."

The 1967 Detroit race riots that killed 43 people left neighborhoods just blocks from the seminary in ashes. Gunfire struck the seminary when a priest observing the chaos from a tower was mistaken for a sniper by a National Guardsman.

An outdoor hallmark alabaster statue of Jesus Christ is pictured at Detroit's Sacred Heart Major Seminary in August 2025. During rioting in 1967, the statue was painted over — Jesus' face, hands and feet were covered in black paint. Then-rector Msgr. Francis X. Canfield decided to keep it that way as a sign of solidarity with the Black community. (Patricia Montemurri)

During the five days of rioting, the seminary's outdoor hallmark alabaster statue of Jesus Christ was painted over — Jesus' face, hands and feet were covered in black paint. Rector Canfield decided to keep it that way as a sign of solidarity with the Black community. It has remained so since 1967.

Five weeks after the assassination of Dr. King in Memphis on April 4,1968, Canfield welcomed civil rights activists participating in the Poor People's March on Washington, who stopped in Detroit May 13-14 by bus from Chicago and Milwaukee. According to a book commemorating Sacred Heart's 50th anniversary, the seminary gave shelter to the march members.

Seminary classes increasingly focused on living out Jesus' teachings by helping the suffering. Cunningham and Fraser took this a step further, launching what became the Focus: HOPE movement. They invited dozens of priests to Sacred Heart to learn how to speak with white congregants about racism. From there, 55 volunteer priests preached special homilies at most archdiocesan churches over three consecutive weekends, often getting negative reactions from white Catholics.

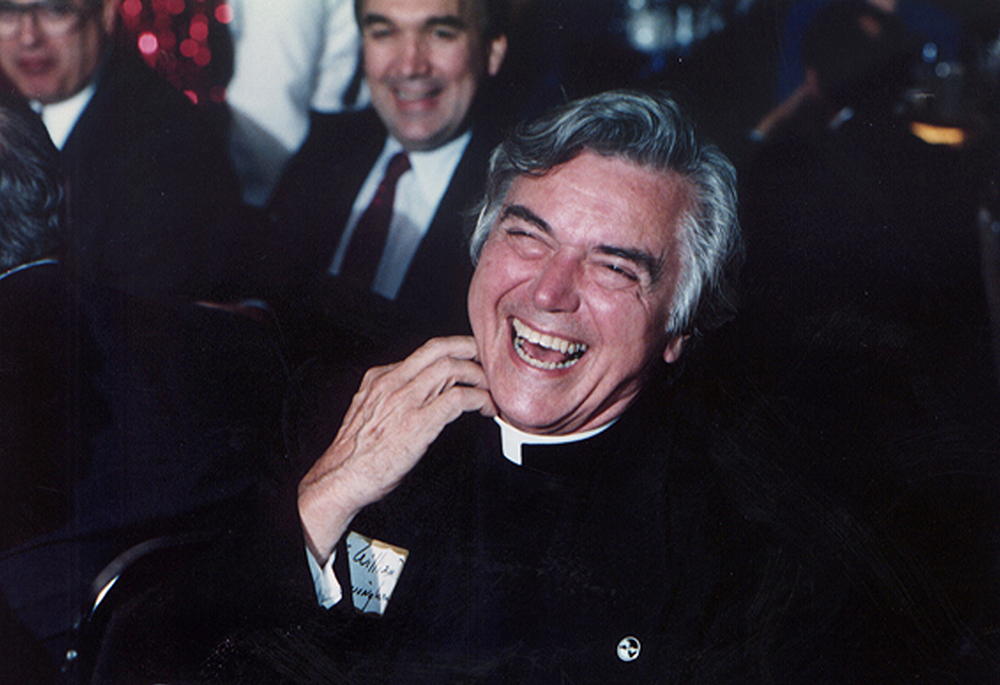

Fr. William Cunningham, co-founder of Focus: HOPE, a ministry to Detroit's poor and jobless, is seen in this undated photo. Cunningham died in 1997. (CNS/Courtesy of Michigan Catholic)

The mission statement of Focus: HOPE said: "Recognizing the dignity and beauty of every person, we pledge intelligent and practical action to overcome racism, poverty and injustice."

Its early initiatives included sending seminarians and suburban housewives undercover to grocery stores in Detroit and the suburbs, to document racial disparities in food quality and pricing.

By 1970, declining enrollment and budget shortfalls led to the closure of Sacred Heart's high school, formally known as Cardinal Mooney Latin School.

The college program continued, with seminarians completing undergraduate studies in Detroit and, for those deemed worthy, moving on to the theologate at St. John's Provincial Seminary in Plymouth, Michigan. At St. John's, Vatican II ideals flourished. Faculty envisioned a church with robust lay involvement. At St. John's, the bent was clearly progressive and liberal.

Several priests who graduated from St. John's said there were frequent discussions about liberalizing the church's teachings on divorce, female clergy and homosexuality, especially under St. John's rector, Fr. Kenneth Untener, from 1977 to 1980, when Untener was made a bishop and chosen to head the Diocese of Saginaw in Michigan.

"They were looking forward to heavy lay involvement in the church, perhaps married priests and women," said Fr. Joseph Gembala, who studied at St. John's during the 1980s and is now pastor of St. Malachy Parish in Sterling Heights, Michigan.

That bent underwent a transformation under the papacy of John Paul II.

Sacred Heart shifts its focus

In 1981, John Paul II appointed Edmund Szoka, then the bishop of the Gaylord, Michigan, Diocese, to become Detroit archbishop. Szoka was a Polish-speaking prelate who became a close confidante to John Paul II. John Paul later made Szoka a cardinal and the so-called "governor" of the Vatican, more formally known as the president of the Pontifical Commission for the Vatican City State.

One of Szoka's first moves came in 1982, when theologian Fr. Anthony Kosnik was pressured to resign from the now-closed Sts. Cyril and Methodius Seminary in a Detroit suburb that trained Polish American priests. Kosnik, a nationally known theologian, was co-author of a controversial book based on a study commissioned by the Catholic Theological Society. The book reviewed the morality of all sexual relationships, including same-sex relationships.

In 1987, Szoka announced the closing of St. John's, remaking Sacred Heart into a "major" seminary. A committee of 10 priests (including future bishops) and one female faculty member rewrote the humanities-laden curriculum for undergraduates.

Sacred Heart offered three graduate degree programs: A Master of Divinity degree for candidates for the priesthood, a Master of Arts in Theology available to priests, religious and laity, and a Master of Arts in Pastoral Studies to prepare students for lay ecclesial ministry. That degree stressed catechetics, pastoral ministry and spirituality. And, for the first time, women would be allowed to work toward a degree at the seminary.

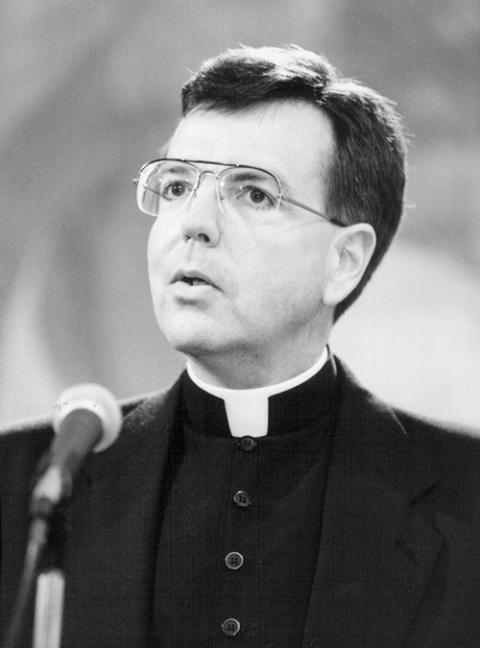

Msgr. Allen H. Vigneron, then-rector and president of Sacred Heart Major Seminary in Detroit, was named auxiliary bishop of Detroit June 12, 1996. (CNS/Douglas Susalla)

Leading the transition were Msgr. John Nienstedt, who was named rector in 1988, and Vigneron, dean of academics. (Nienstedt later became the Minneapolis-St. Paul archbishop and he resigned in 2015, days after prosecutors brought charges against the St. Paul-Minneapolis Archdiocese "for its failure to protect children.")

Vigneron and Nienstedt shifted Sacred Heart's focus to strict adherence to church dogma and dictates from Rome. Faculty considered too liberal were dismissed. Vigneron had taught philosophy and theology at the seminary, beginning in 1985, became its academic dean in 1988 and was the seminary rector from 1994 to 2003, during the archbishop tenure of Detroit Cardinal Adam Maida.

Philosophy professor Carson said Vigneron sent monitors to his classes for signs of anti-Catholic teaching. Eventually, Carson was sacked in 1990 and said he was told it was because of declining enrollment.

In 2003, Pope John Paul II appointed Vigneron as the coadjutor bishop of the Diocese of Oakland, California, and he became head of the diocese later that year. In 2009, Pope Benedict XVI made Vigneron Archbishop of Detroit where he maintained oversight of the seminary.

Seminarians chat outside the chapel at Sacred Heart Major Seminary in Detroit Oct. 5, 2021. (CNS/Detroit Catholic/Marek Dziekonski)

'A seminary in one direction and a pope going in another'

Four years later brought another sea change. In 2013, "then comes Pope Francis and the church swings liberal," said Gembala. In Detroit, "you've got a seminary in one direction and a pope going in another direction."

Michael Einheuser, a 1969 graduate of the seminary high school, served on Sacred Heart Major Seminary's Board of Trustees from 1994 to 2004. Disillusioned with the Catholic hierarchy, Einheuser is now a priest in the Ecumenical Catholic Church of Christ, an international movement of independent Catholics not in communion with Rome or the Archdiocese of Detroit. Einheuser recalls Vigneron's influence as decisive.

"It's fair to say that the big change was at the hand of Allen Vigneron as rector. He was the rector, and nobody would be hired who he didn't approve of. He's a very personable guy. His core beliefs are very conservative theology," Einheuser said.

Einheuser said the board did not get involved in hiring or curriculum, focusing on budget and financials. Seminary leaders, he said, "wouldn't let anybody teach future priests unless they were sure about what their beliefs and values were."

Retiring Archbishop Allen Vigneron hands the crosier, or shepherd's staff, to Archbishop Edward Weisenburger as Archbishop Weisenburger takes his seat for the first time upon the cathedra March 18, 2025, at the Cathedral of the Most Blessed Sacrament, officially becoming Detroit's sixth archbishop and the 10th man to officially lead Detroit's Catholic faithful. (OSV News/Detroit Catholic/Valaurian Waller)

Vigneron reached the mandatory retirement age of 75 in 2023, and Pope Francis accepted his resignation in February this year.

Francis appointed Weisenburger from Tucson, Arizona, where he was known for championing immigrant rights and progressive causes. Weisenburger strongly opposed President Donald Trump's "big, beautiful bill" that diverted funds from social programs to immigration crackdowns.

The dismissals of the three professors follows their public criticisms of Pope Francis and his teachings.

Ralph Martin, a theology professor and director of graduate programs in the new evangelization, was hired in 2002 when Vigneron was seminary rector. Martin has written critically about Pope Francis, saying the late pontiff "has said and done some things that are confusing and seem to have led to a growth of confusion and dissent in the church."

In a statement, Martin said Weisenburger terminated him without giving Martin "any specifics but mentioned something about having concerns about my theological perspectives." Through a spokesperson, Martin declined further comment.

Eduardo Echeverria was hired in 2003 and taught theology and philosophy. In a 2019 revision to his 2015 book Pope Francis: The Legacy of Vatican II, Echeverria wrote that "I have now come to accept that Francis has contributed to the current crisis in the Church — doctrinal, moral, and ecclesial — due to the lack of clarity, ambiguity of his words and actions, one-sidedness in formulating issues, and a tendency for demeaning Christian doctrine and the moral law."

Echeverria has said there was no reason given for his dismissal, and that he's bound by a non-disclosure agreement.

Edward Peters, hired in 2005, is a professor of canon law who had been appointed by Pope Benedict XVI as the first layperson to be a consultant to the Apostolic Signature, the Holy See's highest court.

He announced his teaching contract was terminated via an X social media post. "I have retained counsel. Except to offer my prayers for those affected by this news and to ask for theirs in return, I have no further comment at this time."

Peters had expressed "grave concerns" about Francis' condemnation of the death penalty. He also said Francis had "writing flaws" in Amoris Laetitia when Francis suggested allowing divorce and remarried Catholics to participate in the sacraments again.

Sacred Heart’s 'ultra-conservative' swing

To learn more about the archdiocese and its priests, pastor Gembala said Weisenburger has been having regular dinners with groups of them. The dismissals came four months after Weisenburger arrived in Detroit.

"It was obviously a gravity of such a serious nature, Weisenburger said, 'I'm not going to wait.' And they're preparing for the next school year" at the seminary, said Robert Mickens, a longtime Vatican observer who writes the "Letter from Rome" at UCA News.

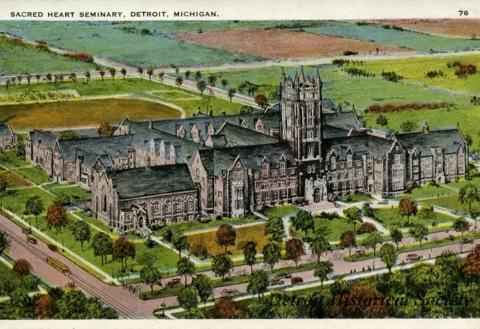

A color postcard circa 1925 depicts an aerial view of Sacred Heart Seminary. (Courtesy of Detroit Historical Society)

Mickens said that "a bishop is under no obligation to give reason for hiring or firing someone who works in his seminary, because the bishop, and solely the bishop, is the one who must answer for the formation and ordination of future priests."

The firings "are an earthquake at the seminary," said Fr. Ron Victor, pastor of St. Isidore Parish in suburban Macomb, Michigan. He said they were needed because Sacred Heart has become "ultra-conservative and it's very clerical."

Victor notes some Detroit Archdiocese priests ordained in recent decades favor more traditional dress, such as cassocks, and make a point of urging parishioners to receive Holy Communion on the tongue.

Earlier this year, Sacred Heart Major Seminary had 28 full-time students and 160 part-time enrollees. It's also once again home to Vigneron, who chose an apartment in the seminary as his retirement residence.

Both Weisenburger and Vigneron declined comment for this story.

"The Archdiocese of Detroit (including its bishops) cannot comment on archdiocesan or seminary personnel matters," said archdiocese spokesperson Holly Fournier.