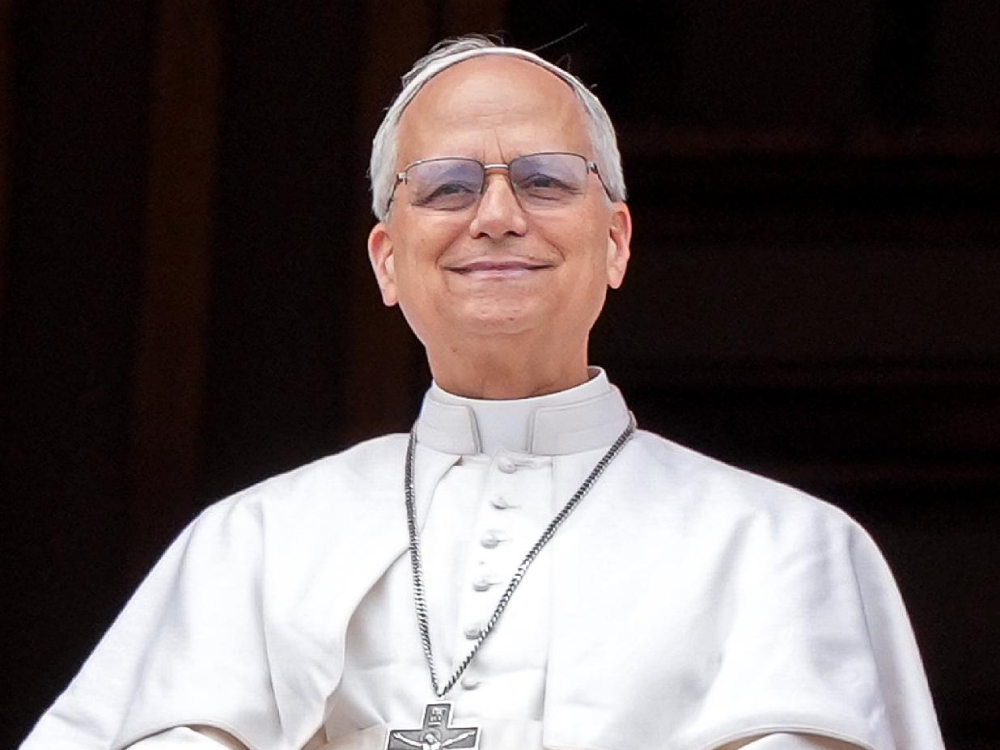

Pope Leo XIV looks out to the crowd from the central balcony of St. Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican as he leads the midday recitation of the “Regina Coeli” prayer for the first time May 11, 2025. (CNS/Lola Gomez)

Today, September 14, Pope Leo XIV celebrates his 70th birthday. God only knows just how many deep dish pizzas, White Sox jerseys and Italian beefs the Chicago-born pope will be receiving as gifts.

But as we celebrate our new pope's first birthday in office, I'm aware of a gift that he's given the church that, so far, has gone almost totally unreported.

About a week after Pope Leo was elected, the Vatican released his official portrait. In the midst of the avalanche of photos that accompany the election of a pope in the modern era, it's hard for any single image to make much of a dent. Perhaps Vaticanistas will pour over the photo for hints of the incoming pope's agenda. Catholic schoolchildren around the world will certainly stare at the image as they walk into school. Otherwise, the parade moves on.

Pope Leo XIV poses for what Vatican Media says is his official portrait, which was distributed May 16, 2025. (CNS/Vatican Media)

But Pope Leo's official portrait is worth a second look, for it represents a radical departure in the way a pope presents himself. The choices in the photo bespeak a pastor intent on connecting with people in a profoundly human way.

The embalming method

For as different as the previous four popes were in their styles, theologies and goals, if you look at the Vatican's official portraits of them upon their elections, there is a striking similarity: The popes do not make real eye contact with us. Pope Benedict XVI stands looking off to the side, with such a pleased look on his face you can't help but wonder what he's looking at. (Everything within me wants to believe it was his cat, Chico.) Pope Francis has his head turned slightly to the right, and his glasses slid down in such a way that we can't really see his eyes. Pope Paul VI, too, seems to be looking slightly off to the right, perhaps to a photographer cheering "Say formaggio!"

Pope John Paul's 1978 portrait is the only one that seems to make eye contact, but still only partially. His torso and head are each facing away from us in different directions, and if he is looking at us, it's only out of the corner of his eyes.

Advertisement

Whether intentional or not, the choice to not look directly into the camera creates an immediate separation between the pope and the viewer. We are quite literally not the focus of their attention. And in the case of John Paul, the strange ambivalences of his physical posture and his facial expression indicate such a guardedness as to make us feel actively repelled. This is a man who definitely wants some space.

The lack of eye contact also withholds much of the vitality of the popes' characters. Benedict's photo does capture his "shy uncle" energy. But Francis' and John Paul's lack the passion and humor of their personalities, and Paul VI's image is so posed he could be in Madame Tussauds. It's telling that, as a group, the portraits mostly resemble Mass cards used for the dead at funerals. There is that selfsame sense of the men as somehow gone, no longer here.

Lacking the ability to connect with their faces, we look elsewhere in the popes' portraits for something to hold onto. Small details of their clothing take on significance — Francis wearing the Good Shepherd cross he'd had since he was an archbishop in Buenos Aires; Pope Benedict choosing to be photographed wearing his Fisherman's Ring. In effect, the portraits instruct us to see the popes first and foremost as objects of interpretation. Paul's photo is the most deliberate in this regard: posing on a throne-like chair, his right hand is in the traditional papal gesture of benediction. Looking closely, that gesture is the crispest, most in-focus element of the whole image.

A promise of friendship

No doubt each of these papal portraits has as much to say about the moment it was done as what a given pope thought of himself of the church: Francis' has the feeling of a guy going along with what is being asked of him, and John Paul's of a man wondering what he's gotten himself into.

Pope Leo's portrait also occurred just days after his election, in similar circumstances, and his portrait has mostly the same basic elements as his predecessors. He's in all white, wearing his pectoral cross, with no real background behind him and his shoulders turned just a hair off center.

Salesian Brother Sal Sammarco poses next to a portrait of Pope Francis at a workshop in Port Chester, N.Y., Aug. 6, 2015. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

But unlike his peers, Leo looks directly at us. And that single difference creates an immediate emotional impact. There is no sense of distance here. Leo seems to be right in front of us in the present moment. And he's not giving us some sort of "official papal" facial expression, oracular distance or warm benevolence, either. There's no sense of authority in his face, or of the photo being posed at all.

Instead, Leo simply looks at us with the emotions he is feeling in the moment: gratitude and love, but also wonder, awe, and an almost tearfulness. It's the portrait of a man to whom something astounding has happened, something that makes him want to get on his knees in gratitude, but also for help. And, incredibly, he is choosing to share that movingly complex set of feelings with us.

A papacy is defined by what a pope does, not by what he wears or whether he smiles in a photo. But if the papacy of Francis taught anything, it was that a pope's impact lies not exclusively in his big policy pronouncements — perhaps not even primarily — but in the endless small public choices he makes. A simple gesture at a moment that others might overlook can preach the gospel with a power that the poets long for.

In his official portrait, Leo saw such a moment, and used it to preach something truly new: the pope as a person like us, emotional, caring, and vulnerable. Other popes may have awed us with their sanctity, or touted their authority. But here is a man so interested in us knowing that we are loved, and that we have a friend in him, he created a lasting expression of those convictions to accompany us. Whenever we're in our parishes or school, retreat houses or offices, or this week as we celebrate his 70th birthday, we can look and find him there, grateful for us and inviting.