Pope Leo XIV gives his homily during Mass on the feast of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in St. Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican June 27, 2025. The pope ordained 32 men from five continents during the Mass (CNS/Lola Gomez)

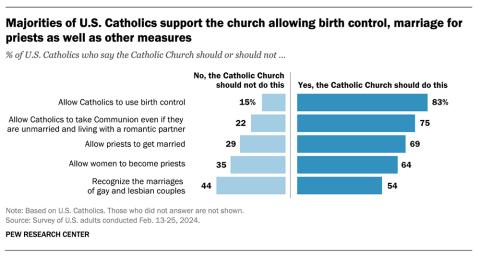

Pope Leo XIV begins his papacy with a historic opportunity to close the growing gap between what the church teaches about sex and gender, and the lived experiences and values of a clear majority of U.S. Catholics.

He can, once and for all, align that teaching with Scripture and enlightened theology, as opposed to the church's deeply ambivalent views of sexuality from the first century, many of which were rooted in Greco-Roman philosophy. Such a shift would transform church doctrine about birth control, same-sex marriage and women's ordination, among other matters.

Leo XIV's handling of such issues, or his choice to overlook them, will carry significant implications for his pontificate and the future trajectory of the Catholic Church.

Despite the early enthusiasm he has inspired, Leo's pontificate is weighed down by urgent expectations. Some believe that the church's moral credibility and spiritual vitality, particularly in the West, are at risk. Two unresolved and gender-connected issues — Catholic teaching on sexuality and the exclusion of women from ordained ministry — expose the fault lines.

On June 25, Leo publicly reaffirmed the tradition of priestly celibacy, calling it a "gift" and an "authentic image of the church." His words, while supporting the ideal, subtly acknowledged the tension between the church's teachings on sexuality and the realities that many faithful clergy and laypeople still deal with.

For decades, surveys, pastoral experience and theological reflection have pointed to a growing rift between official doctrine and the lived experiences and values of the faithful. The gap is too broad to ignore, and church teaching underlines the importance of the alliance between doctrine and what the faithful experience and believe.

Leo's leadership will be tested by how he addresses these matters — not simply through rhetoric, but also through action rooted in Gospel values, human dignity and communal discernment.

But the road to reform will not be without peril. Any serious movement by Leo toward reexamining or reversing long-held church teachings on sexuality, particularly regarding contraception, same-sex relationships or the ordination of women, would almost certainly provoke intense resistance. Parts of the church, especially within the hierarchy and the Global South, could view such steps as a capitulation to secular pressures and doctrinal betrayal.

Sexual ethics

The modern sexual ethics debate entered a significant phase in 1963, when Pope John XXIII established a papal commission to study birth control. Pope Paul VI later expanded the commission to include theologians, bishops and married lay Catholics.

Despite the commission's majority recommendation that artificial contraception could be morally permissible in some instances, Paul issued the encyclical Humanae Vitae in 1968, reaffirming a strict ban. He insisted that every marital act must remain open to the transmission of life.

The backlash was immediate and far-reaching. Within hours, Fr. Charles Curran, then of the Catholic University of America, led 86 fellow theologians to issue a statement of dissent, affirming the primacy of individual conscience. Within weeks, more than 600 Catholic theologians followed suit.

The theologians asserted Catholics could, in good conscience, disagree with the noninfallible teachings of Humanae Vitae. They supported the primacy of individual conscience, criticizing the encyclical's reliance on a narrow and excessively biological interpretation of natural law. They challenged the encyclical's core principle — the "inseparable connection" between the unitive and procreative aspects of every single marital act.

Critics of Humanae Vitae argued that it failed to consider intention, circumstance and the broader significance of sexual intimacy in marriage. By focusing solely on procreation, the encyclical neglected the personal, relational and unifying aspects of sexuality.

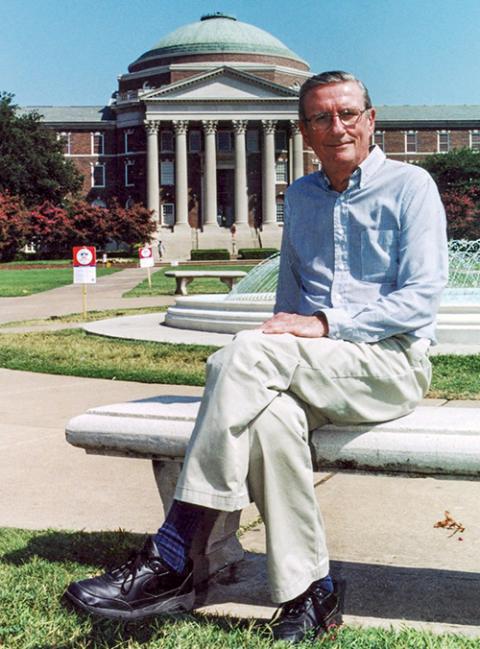

In the 1980s, the Vatican formally investigated Curran for his public dissent from the church's official teachings. The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (currently called the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith), then led by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI), concluded that Curran's views were incompatible with his role as a Catholic theology professor.

Fr. Charles Curran at Southern Methodist University in Dallas in 2000 (CNS/Texas Catholic/Robert Bunch)

Despite Curran's defense that theologians could legitimately challenge noninfallible teachings within the tradition, the Vatican declared him unfit to teach Catholic theology. In 1986, following a declaration by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Catholic University revoked Curran's authorization to teach theology, formally ending his tenure in 1987. He later joined the faculty at Southern Methodist University, where he taught for decades.

The core theological principle in Humanae Vitae affects not just those who may consider using birth control, but also others in the church, especially LGBTQ communities. The Catechism of the Catholic Church affirms the dignity of all people but describes homosexual acts as "intrinsically disordered," partly because such acts are not linked to "the gift of life."

In some dioceses, clergy receive training in empathetic accompaniment, and LGBTQ ministries have offered spaces of refuge. Yet without structural reform or doctrinal reexamination, such gestures may appear tokenistic.

Humanae Vitae had a significant impact on Catholic beliefs and practices. The church's credibility — and even its relevance — was dramatically affected. In the wake of Humanae Vitae, surveys and sociological studies reported a sharp decline in both Mass attendance and the use of the sacrament of confession, especially among younger Catholics.

Many began turning instead to their conscience, a shift that signaled not a rejection of faith, but a reevaluation of authority in moral decision-making.

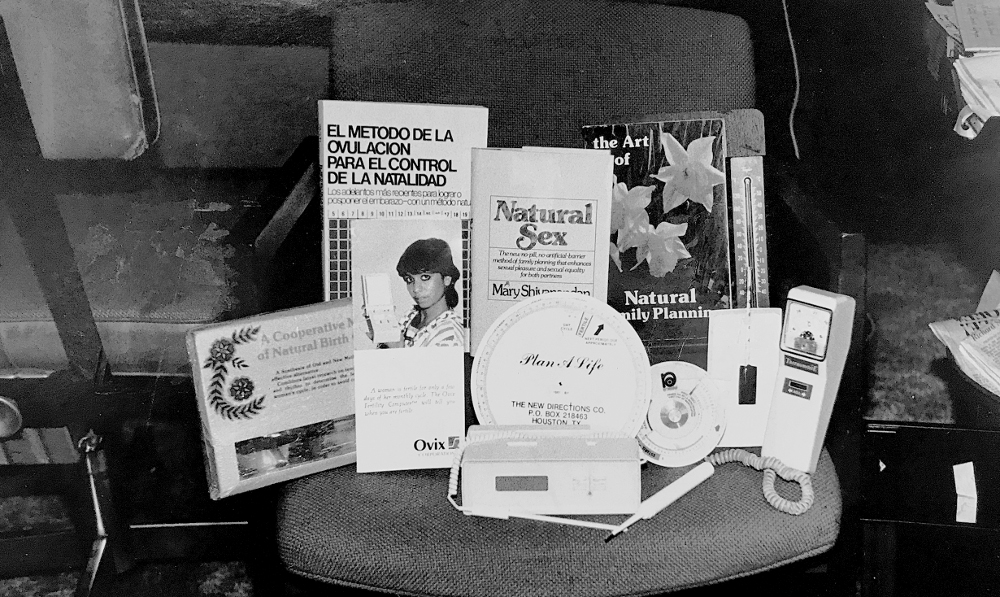

According to surveys by the Guttmacher Institute and Catholic sociological research in the early 2000s, more than 90% of sexually active U.S. Catholic women were ignoring church birth control teachings; fewer than 3% were practicing natural family planning, the only method of avoiding pregnancy sanctioned by the church.

Natural family planning paraphernalia, circa 1983 (NCR photo/Arthur Jones)

This rupture between official teaching and practice, in theory, is not supposed to happen. Catholic tradition emphasizes that authentic teachings should be discerned in harmony between the hierarchy and the faithful — a principle known as the sensus fidelium (sense of the faithful), reaffirmed in Lumen Gentium, which states that the people of God "cannot err in matters of belief" when they are united in faith and morals.

Historical roots

The church's deeply ambivalent views on sexuality trace back to the earliest centuries of Christianity and were profoundly shaped by Greco-Roman philosophical traditions, particularly Stoicism and Platonism. Both schools regarded bodily pleasure — especially sexual pleasure — with caution, associating it with moral weakness and spiritual distraction.

The Stoics taught that virtue lay in mastering one's passions, cultivating reason and self-discipline as paths to wisdom. Plato's dualistic metaphysics elevated the soul over the body, viewing the latter as a temporary vessel and an obstacle to truth. These philosophies found a natural affinity with early Christian asceticism, which idealized celibacy, virginity and martyrdom as signs of holiness.

Sexual desire was considered both immoral and a danger to one's spiritual well-being. Early church fathers such as Tertullian and Jerome expressed open suspicion toward the flesh, extolling virginity as a higher calling and frequently portraying marital sex as a necessary but regrettable concession to human frailty.

Artists' depictions of church fathers and doctors of the church, from left: Tertullian (KU Leuven Libraries Special Collections); St. Jerome (Wikimedia Commons/Samuel H. Kress Collection); St. Augustine (OSV News/The Crosiers/Gene Plaisted); St. Thomas Aquina (OSV News/Nancy Wiechec)

St. Augustine of Hippo, writing in the fourth and early fifth centuries, gave enduring theological shape to these ascetic currents. A former adherent of Manichaeism — a belief system that sharply divided spirit from flesh — Augustine brought a profound personal struggle with sexual desire into his Christian theology.

In his view, concupiscence, or disordered desire, was a wound inflicted by original sin. Even within marriage, he believed, sexual acts were tainted by this disorder unless conducted with restraint and directed solely toward procreation. Pleasure in sex, even between spouses, was approached with suspicion and often linked to guilt.

While Augustine affirmed certain goods of marriage — fidelity, the bearing and raising of children and sacramental unity — he nonetheless taught that sexual acts always bore the mark of humanity's fallen condition. This framework, emphasizing restraint over joy, would shape Christian sexual ethics for centuries to come, embedding a persistent tension between bodily love and spiritual virtue.

In the 13th century, Thomas Aquinas sought to synthesize Christian doctrine with Aristotelian philosophy, resulting in a more systematized moral framework based on natural law. Aquinas taught that the "natural end" of sexuality was procreation and that any sexual act must be "ordered" toward this biological purpose to be morally good.

While he recognized the unitive dimension of sexual intimacy — the deepening of love and mutual commitment between spouses — he consistently subordinated it to the procreative imperative.

This synthesis led to a rigid moral taxonomy in which acts such as masturbation, contraception, oral or anal sex and any ejaculation outside vaginal intercourse were condemned as "intrinsically disordered," regardless of the couple's intent, love or marital status. Over time, this biologically deterministic framework ossified, reducing moral reflection to a checklist of violations, focusing more on physical outcomes than on personal conscience, mutuality or the spiritual meaning of sexual love.

During the Counter-Reformation, as Protestant reformers challenged the moral authority of the Catholic Church, the Council of Trent (1545-63) responded with a renewed emphasis on orthodoxy and institutional discipline. In this climate, seminaries were established to train clergy with precise theological and moral instruction.

From this effort arose the "manualist" tradition — a school of moral theology based on detailed handbooks for confessors. These manuals presented ethics in casuistic terms, cataloging sins by type and severity and evaluating actions primarily by their external conformity to natural law.

Interior intention, personal conscience, psychological maturity and relational context were often overlooked. Marriage was frequently depicted less as a covenant of mutual joy and more as a legitimate outlet for otherwise dangerous lust.

This legalistic approach dominated Catholic sexual ethics well into the 20th century, reinforcing a view of sexuality not as a gift to be embraced with reverence but as a domain to be policed with suspicion.

Advertisement

Lay voices

Starting in the 1960s and expanding rapidly after the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), lay theologians — especially women — began to enter the field of moral theology, bringing fresh insights rooted in experience, relational ethics and personal discernment. They emphasized mutuality, the significance of intimacy and the formation of conscience.

Theologian Margaret Farley, among others, has written that the moral value of sexuality must be measured not simply by biological effects, but by the quality of relationship, love, justice, and the degree of mutual respect and care. This marked a shift away from a strictly law-based moral system to one grounded in human dignity, love and responsibility.

These theologians raised challenging and pastoral questions: Could a choice of contraception be morally justified if made in love and through mutual discernment? What if the act strengthens the couple's union and promotes the family's well-being? Can justice within marriage require spacing children for reasons of health, economic stability or emotional balance?

From left: Mercy Sr. Margaret Farley in an undated photo (CNS/Courtesy of Yale Divinity School); St. Joseph Sr. Elizabeth Johnson in 2011 (NCR photo/Jan Jans); Phyllis Zagano in 2019 (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

Theologian Christine Gudorf has written that the Christian tradition must seriously consider the goodness of the body, the holiness of pleasure and the moral significance of maintaining loving and faithful relationships.

Although the Catholic hierarchy has rejected these insights, they reflect a broader evolution in Catholic moral theology. The lived experiences of married couples, particularly those of women, are increasingly informing theological reflection.

Theologian Lisa Sowle Cahill has insisted that experience, particularly the experience of women, is not opposed to tradition; rather, it is part of it — an ongoing source of theological reflection and moral insight. These contributions are not merely acts of dissent; they represent genuine development, rooted in tradition, focused on justice and reflecting the Gospel's call to human flourishing.

Ordination of women

The second central fault line concerns the role of women in the church. While women serve as theologians, pastoral leaders, educators and even Vatican officials, they are still barred from priestly ordination.

The church's official position was reaffirmed in Ordinatio Sacerdotalis (1994), when Pope John Paul II declared that the church has no authority to ordain women and that this teaching requires the "full and unconditional assent" of the faithful. The rationale rests on the claim that Jesus chose only male apostles and that only men can act in persona Christi — in the person of Christ — during the Eucharist.

Priests join in prayer during Mass with Pope Leo XIV on the feast of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in St. Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican June 27, 2025. (CNS/Lola Gomez)

Feminist theologians and lay Catholics, among others, have challenged these conclusions. They argue that Jesus' choice of male apostles reflects the social and cultural norms of his historical context, not a timeless theological mandate. They cite Scripture, pointing to numerous women in leadership roles — Phoebe, a deacon (Romans 16:1); Junia, "prominent among the apostles" (Romans 16:7); as well as others who hosted house churches, preached the Gospel and prophesied in early Christian communities.

Theologian and St. Joseph Sr. Elizabeth Johnson credits patriarchy, hierarchy and dualism as cultural patterns that became ingrained in religion and constrained women's full voice in theology. Likewise, Phyllis Zagano argues that the church has overlooked its tradition, pointing out that history shows that women served as deacons in the early church for centuries, receiving rituals of commissioning that many scholars consider to have been ordinations.

A 1992 Gallup poll found that two-thirds of American Catholics supported the ordination of women. More recent synodal surveys, including a Vatican-commissioned global listening project, echo those findings.

In 1995, the U.S. Jesuits issued a statement admitting complicity in reinforcing male domination and clericalism, asking God for the "grace of conversion." Yet, the church hierarchy has responded mainly with silence or reaffirmation of the status quo.

This silence has pastoral consequences. Women already lead approximately 75% of parishes without resident priests in the U.S. They serve as chaplains, educators, pastoral associates and spiritual directors. Many Catholics question how the church can continue to deny sacramental leadership to the very women who keep its ministries alive.

Francis' pastoral guidance before Leo XIV

Pope Francis faced the same sex- and gender-related issues, but largely skirted them by offering pastoral guidance rather than doctrinal reform. Famously, when asked in 2013 about a gay lobby in the church, he replied, "Who am I to judge?" The comment was widely praised for its tone, yet it left church teaching untouched.

People gather for a rooftop reception at St. Francis of Assisi Church in New York City following the annual "Pre-Pride Festive Mass" June 29, 2024. The liturgy, hosted by the parish's LGBT+ ministry, is traditionally celebrated on the eve of the city's Pride parade. (OSV News/Gregory A. Shemitz)

Francis established two commissions to study the possibility of ordaining women deacons. Each comprised respected theologians and historians, and both reportedly produced inconclusive findings. Francis reported that the commissions did not reach a consensus and stated that the church's authority on the matter remained unclear, showing the need for further study.

On sexual ethics more broadly, Francis emphasized the importance of conscience, accompaniment and discernment — key themes in his 2016 apostolic exhortation, Amoris Laetitia. While this approach softened the rhetoric, it did not change official teaching on contraception, same-sex relationships, or the role of women in ministry.

As a result, many reform-minded Catholics admired Francis' pastoral tone but were disappointed by the lack of concrete change. The gap between the church's official positions and the lived realities of many Catholics remains unaddressed. Francis opened the doors, but Leo XIV now has to decide whether to walk through them.