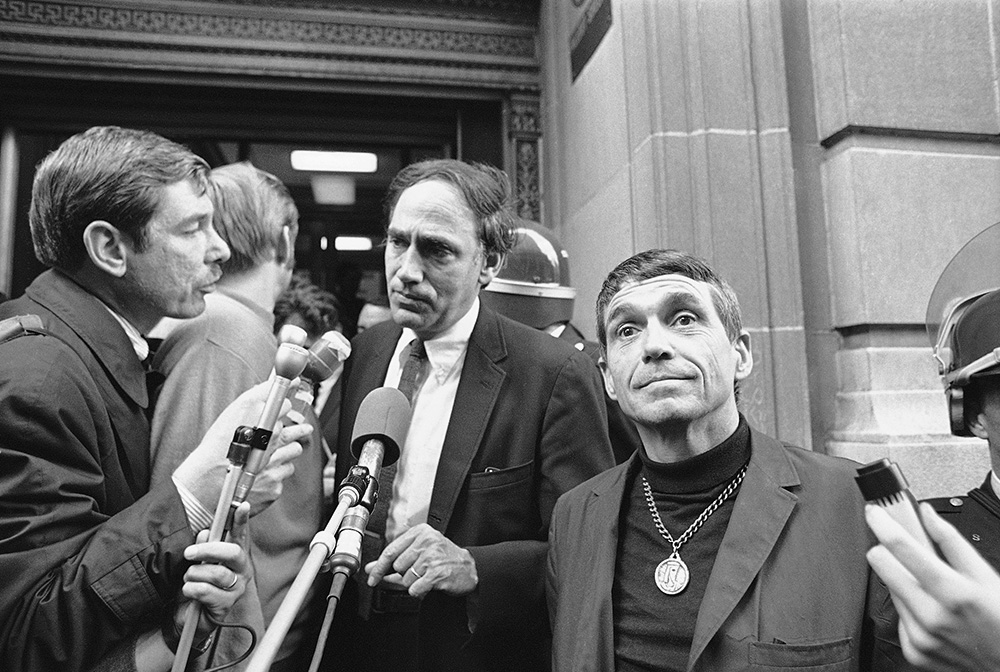

Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan, right, and William Kunstler, defense lawyer, talk with reporters in Baltimore Nov. 9, 1968, after the trial and conviction of the Catonsville Nine. In May that year, Berrigan and eight other Catholics broke into a Selective Service office outside of Baltimore and burned 378 draft files — while reciting the Lord's Prayer — to protest the Vietnam War. (AP/William A. Smith)

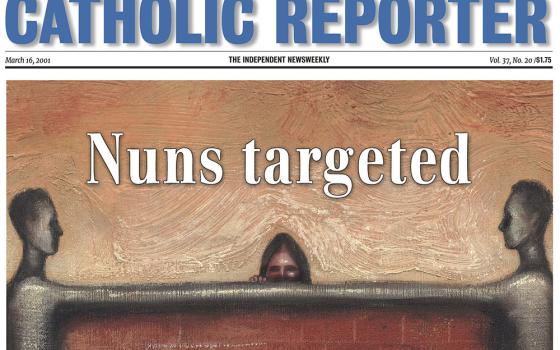

(NCR logo/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

One of the most tumultuous years for the nation — and the U.S. Catholic Church — in the 1960s was 1968, and that tumult was reflected in the pages of the National Catholic Reporter.

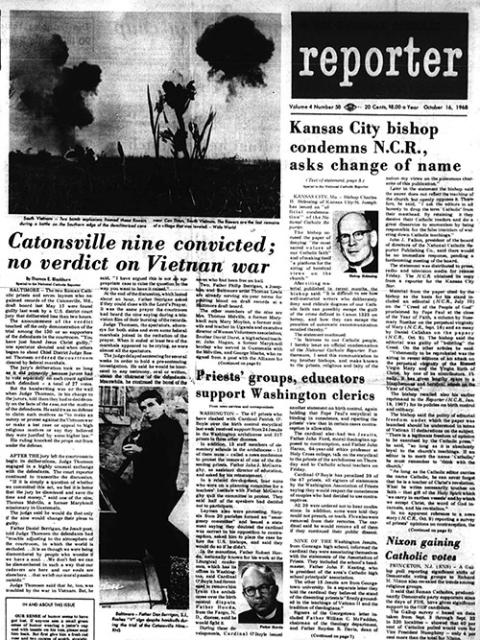

The lead story on Oct. 16 was the condemnation of NCR by Bishop Charles Helmsing of Kansas City-St. Joseph, Missouri, and his demand that we drop the word "Catholic" from the name of this newspaper. (We declined.)

Another story reported on Washington Cardinal Patrick O'Boyle's clash with 47 priests who dissented from the Vatican's then-just-released Humanae Vitae encyclical prohibiting the use of birth control.

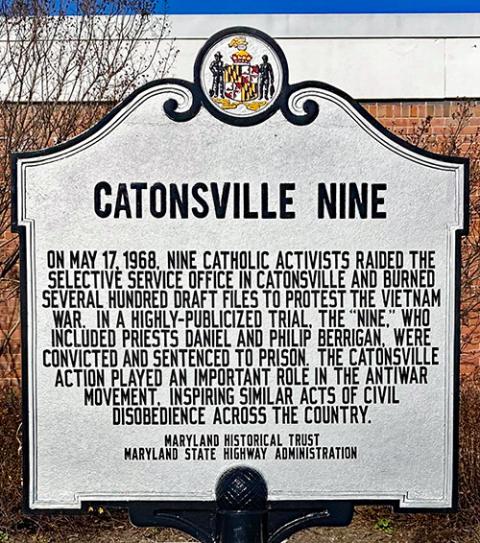

Another top story was on the trial and conviction of the Catonsville Nine. They were the Catholic activists who broke into a Selective Service office outside of Baltimore and burned 378 draft files — while reciting the Lord's Prayer — to protest the Vietnam War. Among them the famous Berrigan brothers — Josephite Fr. Philip Berrigan and his brother Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan.

For our continuing series on the 60th anniversary of NCR, we republish the story on the conviction of the Catonsville Nine.

Catonsville nine convicted; no verdict on Vietnam war

By Thomas E. Blackburn

Oct. 16, 1968

BALTIMORE — The two Roman Catholic priests and seven laymen who napalmed records of the Catonsville, Md., draft board last May 17 were found guilty last week by a U.S. district court jury that deliberated less than two hours.

The announcement of the verdict touched off the only demonstration of the trial among the 130 or so supporters of the defendants in the courtroom. "You have just found Jesus Christ guilty," one spectator shouted and when others began to shout Chief District Judge Roszel Thomsen ordered the court room cleared by federal marshals.

The jury's deliberation took as long as it did primarily because jurors had to vote separately on each count against each defendant — a total of 27 votes.

But the handwriting was on the wall when Judge Thomsen, in his charge to the jurors, told them they had to decide only on the facts of the case, not the motives of the defendants. He said it was no defense to claim such motives as "to make an outcry or protest against the Vietnam war or make a test case or appeal to high religious motives or say they believed they were justified by some higher law."

His ruling knocked the props out from under the defense.

Detail from the cover of the Oct. 16, 1968, edition of the National Catholic Reporter (NCR files)

After the jury left the courtroom to begin its deliberations, Judge Thomsen engaged in a highly unusual exchange with the defendants. The court reporter continued to transcribe the discussion.

"If it is simply a question of whether we committed this act, we feel it is better that the jury be dismissed and save the time and money," said one of the nine, Thomas Melville, a former Maryknoll missionary in Guatemala.

The judge said he would do that only if the nine would change their pleas to guilty.

Fr. Daniel Berrigan, the Jesuit poet, told Judge Thomsen the defendants had "trouble adjusting to the atmosphere of the courtroom, in which the world is excluded ... It is as though we were being dismembered by people who wonder if we have a soul ... We don't feel we can be dismembered in such a way that our cadavers are here and our souls are elsewhere ... that we left our moral passion outside."

Judge Thomsen said that he, too, was troubled by the war in Vietnam. But, he said, "I have argued this is not an appropriate case to raise the question in the way you want to have it raised."

At the end of the discussion, which lasted about an hour, Berrigan asked if they could close with the Lord's Prayer. It was the same prayer the courtroom had heard the nine saying during a television film of their burning of the records.

Judge Thomsen, the spectators, attorneys for both sides and even some federal marshals joined in the recitation of the prayer. When it ended at least two of the marshals appeared to be crying, as were almost all the spectators.

The judge delayed sentencing for several weeks in order to hold a pre-sentencing investigation. He said he would be interested in any testimony, oral or written, about the character of the defendants. Meanwhile, he continued the bond of the seven who had been free on bail.

Two, Fr. Philip Berrigan, a Josephite, and Baltimore artist Thomas Lewis are already serving six-year terms for pouring blood on draft records at a Baltimore draft board.

The other members of the nine are Mrs. Thomas Melville, a former Maryknoll nun; Mary Moyla, a former midwife and teacher in Uganda and executive director of Women Volunteers association; Br. David Darst, a high school teacher; John Hogan, a former Maryknoll brother who served in Guatemala with the Melvilles, and George Mische, who resigned from a post with the Alliance for Progress in opposition to U.S. policy in Latin America.

The Catonsville Nine burn draft files outside of a Selective Service office in Catonsville, Md., May 17, 1968. (CNS/www.catonsville9.org)

Each of the nine was convicted of two counts of destroying government property and one count of interfering with the operation of the Selective Service system. Maximum sentence that could be imposed on each defendant is 18 years in prison.

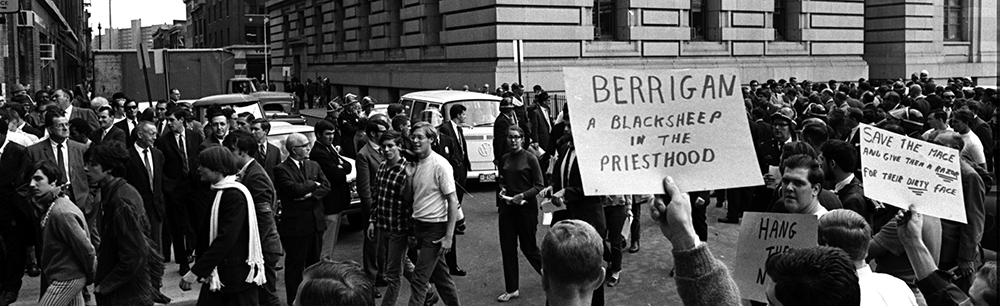

The trial opened Monday, Oct. 7, with anti-war pickets marching outside the courthouse. The same day Negroes demonstrated at city hall against the city council's rejection of the mayor's selection of a black activist to fill a city post, and elements of both groups converged that night on a rally featuring George Wallace.

The only arrests were made at the Wallace rally, but squads of police wearing riot helmets were lined up on nearly every downtown street and policemen with dogs or mounted on horses were scattered throughout downtown. Police shifts were lengthened from the normal 8 hours to 12 hours in order to put more men on the street.

Inside the courtroom, on the fifth floor of the post office building, supporters of the Catonsville Nine gave the defendants a two-minute standing ovation when they arrived for the trial. Judge Thomsen arrived a few minutes later and greeted everyone with a cheery "good morning."

The ovation and the "good morning" were the trial's opening theme each day but the ovation got longer as the trial went on.

One floor below the courtroom, federal marshals held the crowd of people seeking admittance at bay, allowing one person to go up each time one came down. The courtroom holds about 120 spectators tightly packed.

Among those who got in for the opening of the trial were Dorothy Day, cofounder of the Catholic Worker movement, in a blue bandana; Episcopal Bishop James E. Pike, who holds a law degree and was permitted to join the defense counsel.

Before the week was over, a procession of big names in intellectual circles passed through Baltimore, among them Rabbi Abraham Heschel of Jewish Theological seminary in New York city, sociologist and pacifist Gordon Zahn; theologian Harvey Cox; author and philosopher Michael Novak; Noam Chomsky, one of the intellectual fathers of the draft resistance movement; Journalist I. F. Stone, and Howard Zinn, who accompanied one of the defendants, Fr. Daniel Berrigan to Hanoi early this year to accept the release of three American fliers who were shot down over North Vietnam.

The Catonsville Nine were tried in federal court in Baltimore in October 1968. Large demonstrations occurred outside the Federal Courthouse during the trial. (CNS files)

Many were on hand to testify that it is possible for a reasonable man to oppose the war in Vietnam on moral or legal grounds — part of chief defense attorney William M. Kunstler's strategy.

But the government's representative, chief deputy district attorney Arthur Murphy, conceded the point so Kunstler didn't introduce his witnesses.

Kunstler contended that Murphy's position represented a first-time concession by the government in a case like this. "If it is reasonable for an American to believe the war is illegal, then it is equally reasonable for him to take the necessary action to stop the continuing illegality," he said.

Murphy denied it was a "concession."

"To clear the record," he said, "I don't accept his (Kunstler's) use of the word concession ... The government has never taken the position that a person who takes the view that the war is illegal was unreasonable."

The point was important to Kunstler, a veteran of controversial cases, whose hair is long in back and non-existent in front, as if he had moved his scalp backward by constantly rubbing his hand on his forehead.

He opened by saying that far from denying the government's case, the defendants were admitting they did "everything the government says they did. They are not ashamed of it. In fact, they consider it one of the shining moments of their lives."

He also said the defendants were unconcerned about the jury, and wouldn't take part in its selection, an unusual action. He explained later that the defendants believed they would be convicted anyway and that "no jury today could handle the issues we are raising. Or to put it another way, any 12 people could do just as well as any other 12."

Advertisement

At first, he declined even to come to the bench for private conferences between the judge and counsel over jury selection, but later he modified his position and went to the bench "out of respect for the court" without taking part in the conversations.

Judge Thomsen, with avuncular patience, did all of the questioning of the jurors and Murphy tacitly accepted the situation by not asking follow up questions as he could have; however, the government did exercise its right to strike prospective jurors from the panel. Finally, seven women and five men were seated.

On the second day of the trial Kunstler revealed the direction his defense would take and laid bare the issue that would run through the case.

The government held that it was sufficient to prove that the nine had deliberately taken the draft board's files and burned them. The government did not deny the defendants' sincerity nor, by the third day if not before, their rationality. It did, however, argue that what they did broke the law.

Kunstler argued that he had a case like the trials of Jesus and Socrates, whom he mentioned twice in a short opening statement. His clients, he said, had broken a law but their intent was not criminal so what they did was not a criminal act.

"The common law has always recognized that criminal culpability requires the concurrence of an evil-meaning mind with the evil-doing hand," he argued in a brief to the court on this point.

The government objected to this line of argument and Judge Thomsen made it clear he wasn't buying it yet. But he allowed testimony along that line pending his decision on the defense's brief.

His position set the stage for regular government objections that the defendants' testimony wasn't material and for the judge's repetition of his promise that he would "instruct the jury later on whether and to what extent this evidence may be considered."

The prosecution's case was brief. Two employees of the draft board testified that 387 files had been taken (not the earlier reported 600). Mrs. Mary Murphy, chief clerk, said she was cut on the hand and leg trying to wrest away wire baskets of records from Berrigan and Mische.

Another clerk, Mrs. Phyllis Morsberger, said she broke a window trying to take the telephone away from Miss Moylan.

Under cross examination, the defense counsel tried to get into the record that some of the defendants had later sent flowers to Mrs. Murphy, but Judge Thomsen ruled the question out of order. "We are not trying the defendants for their manners, either good or bad," he said.

(Later, when Mische testified he had talked to 80 Roman Catholic bishops about U.S. involvement in Latin America and was met with apathy, Judge Thomsen cut him off saying, "We are not here to try the Roman Catholic bishops."

(Still later, he interrupted Melville to tell him, "We are not here to try the history of Latin America."

(The defense was clearly trying too many things for both the judge and Murphy but Murphy let it go with only pro forma objections, and Judge Thomsen was patient until late in the day when there would be an edge in his admonitions to defense attorneys to speed things up.)

The other highlight of the prosecution's case was the presentation of television film of the raid which showed the records igniting and the prayer service conducted by the raiders. The government had proposed merely to show the film but the defense insisted on the sound portion, too, which included prayers by the participants ("That he make it more difficult for men to kill one another," prayed Berrigan) and the recitation of the Our Father.

A historical marker is seen in 2020 in Catonsville, Maryland, near the site of the former Selective Service Office. (Wikimedia Commons/Monceau)

The film was shown twice — once without the jury present so the defense could see it and raise any objections. Because only half of the spectators could see the screen, they shifted seats in the courtroom while the jury returned so those who had missed it would be in position to see it the second time. There was no demonstration from spectators during the film.

Each of the nine then testified and the testimony followed parallel lines. Each started with his early life and education, then spoke of the specifics of how they came to the conclusion that the Catonsville action was necessary.

The lead-off witness, Darst, held his reasons down to two, which pretty well covered everyone else's: "Basically," he said, "the two intentions would be to, first, raise an outcry over what I saw as a very clear crime, a very clearly unnecessary suffering, a very clear wanton human slaughter ... Second, doing a very tiny bit to stop the machine of death that I saw moving ... like a Czech throwing bricks into tank wheels and sometimes his puny effort stops the tank and that's one less tank."

Artist Thomas Lewis said, "My intent in going there (to Catonsville) was to save the lives of 1-As." Judge Thomsen interrupted. "Wouldn't someone else have been sent? If a call had gone out, and those particular registrants could not be called. Wouldn't someone else have been called?"

"Why, your honor?" Lewis blurted. "Why does it have to be like this?"

The judge didn't pursue it, and Lewis was permitted to step down from the stand. Mary Moylan, wearing a white-on-red arm band with "Milwaukee 14" on it, testified: "I think we must have laws as guides ... But when they are inhuman and when what they protect is imperialism or murder then they are wrong ... There is an imperative — that you act on what you say you believe. We have to not only talk about this, but we have to do something about it."

Mrs. Melville said she had gone to Catonsville because "we've been talking about the war in Vietnam for six years and it keeps getting worse ... it's going to happen in Guatemala and I know those people; they're not just statistics to me."

Berrigan's testimony came last and it was the longest. It included a reading of his meditation on the Catonsville incident (N.C.R., May 29) and of a poem, "Children in the Shelter," from his new book, Night Flight to Hanoi. Kunztler quoted the poem again at the end of his summation.

Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan (left) and his brother Philip Berrigan (center) leave the federal courthouse in Hartford, Conn., Dec. 14, 1970. The brothers served terms at a federal prison in nearby Danbury for destroying draft records. (CNS file)

Berrigan testified at one point: "I burned some paper because I was trying to say that the burning of children was unbearable." He continued by saying that he was acting on behalf of the jury. "I didn't want the children or the grandchildren of the jurors burned by napalm."

Judge Thomsen sharply criticized that statement as being beyond what was in Father Berrigan's mind last May and a play for the jury's sympathy. The priest replied that he was "trying to be concrete. The great sin in modern war is that it makes concrete things — like death and human life — abstract. ... I was trying to be concrete about death because death is a concrete fact, just as I have tried to be concrete in my life about God, who is not abstract."

All in all, the defense's testimony added up to a catalogue of allegations of U.S. imperialism in Vietnam, Guatemala, Africa and the nation's cities. At one point. Judge Thomsen asked Melville: "Do you mean that the U.S. government is executing Guatemalans?"

"Yes, your honor," Melville replied simply.

A coalition of peace organizations and free-lance demonstrators staged a series of marches outside while the trial was going on and nightly rallies at St. Ignatius church with the Catonsville Nine and others as speakers. (Dorothy Day started out: "I hadn't expected to be invited to speak. I'm over 30, you know)

The biggest turn-out was on the opening day of the trial when 1,500 marched, and later picketed the courthouse. Technically, picketing a federal trial is illegal but the police accepted the demonstrators' explanation that the picketing was "informational" for the people of Baltimore and not designed to influence the trial.

On the second day, 300 demonstrators delivered a small coffin to the Customs House, scene of the blood-pouring incident for which Berrigan, Lewis and two others were convicted. The coffin, they said, symbolized the dead on both sides in the Vietnam war.

That night more than 20 draft cards were burned at the St. Ignatius rally. The following day another one went up in flames on the courthouse steps. Police and marshals made no attempt to intervene or make arrests, but the demonstrators planned to publicize the names of the burners anyway.

The Baltimore police were conspicuously restrained during the demonstrations, which were billed in part as a protest in "Agnew country." On several occasions, police had to act to keep demonstrators and hecklers, including Wallace supporters, apart. But they made no arrests and there were no complaints of police brutality.